Godzilla (Gojira)

In the long and storied history of monster movies, there are two which are often considered the absolute cream of the crop, both in quality and historical significance. The first, of course, is the groundbreaking classic King Kong from 1933, and the other is this 1950's masterpiece from the Land of the Rising Sun. It's amazing to think that, despite the unparalleled commercial success it had when it was released in Japan in 1954, as well as the incredible franchise it started, Godzilla was initially dismissed by Japanese film critics of the time, with some going as far as to describe it as "grotesque junk." And yet, as time has gone on, it's accumulated more and more accolades, including being put on several lists of the best Japanese films ever made. Yes, ironically, the Big G's reputation over here was, for a while, no different from how it was in his home country. In any case, I, like most Americans, assumed for a long time that Godzilla, King of the Monsters, the 1956 American version with Raymond Burr, was the one and only version of this original film, but I eventually learned that was not the case at all. I can't recall exactly when I learned that but I think it was when the original Japanese version was given a limited theatrical release in America in 2004 and I saw the reviews and plot synopses that I began to realize they weren't talking about the film I'd grown up with (note: "Stuff I Grew Up With" is among the labels for this review and will also be present for a good chunk of these films but, obviously, I'm talking about the American versions). Reading up how this original version was darker and dealt with themes and allegory concerning the atomic bombings Japan experienced at the end of World War II really piqued my interest and made me wish I could see it. Unfortunately, that theatrical release was too limited for me to have any chance of catching it, and when no DVD followed afterward, I figured it was unlikely I would ever see the original Godzilla the way it was meant to be viewed.

In the long and storied history of monster movies, there are two which are often considered the absolute cream of the crop, both in quality and historical significance. The first, of course, is the groundbreaking classic King Kong from 1933, and the other is this 1950's masterpiece from the Land of the Rising Sun. It's amazing to think that, despite the unparalleled commercial success it had when it was released in Japan in 1954, as well as the incredible franchise it started, Godzilla was initially dismissed by Japanese film critics of the time, with some going as far as to describe it as "grotesque junk." And yet, as time has gone on, it's accumulated more and more accolades, including being put on several lists of the best Japanese films ever made. Yes, ironically, the Big G's reputation over here was, for a while, no different from how it was in his home country. In any case, I, like most Americans, assumed for a long time that Godzilla, King of the Monsters, the 1956 American version with Raymond Burr, was the one and only version of this original film, but I eventually learned that was not the case at all. I can't recall exactly when I learned that but I think it was when the original Japanese version was given a limited theatrical release in America in 2004 and I saw the reviews and plot synopses that I began to realize they weren't talking about the film I'd grown up with (note: "Stuff I Grew Up With" is among the labels for this review and will also be present for a good chunk of these films but, obviously, I'm talking about the American versions). Reading up how this original version was darker and dealt with themes and allegory concerning the atomic bombings Japan experienced at the end of World War II really piqued my interest and made me wish I could see it. Unfortunately, that theatrical release was too limited for me to have any chance of catching it, and when no DVD followed afterward, I figured it was unlikely I would ever see the original Godzilla the way it was meant to be viewed.

So, you can imagine my surprise when, in the fall of 2006, I was browsing around Hastings and saw Classic Media's recently released two-disc edition that had both the original Japanese version and the American King of the Monsters. I hadn't heard anything about this at all and so, as I said back in my Godzilla introduction, when I saw it, I almost fell right on my ass. I couldn't believe this version I'd heard so much about over the past couple of years was now readily available for me to see for the first time (I even saw it at Wal-Mart later on that evening, which I really was not expecting!). That said, I would have to wait a couple of months before I could see it, since it was getting close to Christmastime and I always stop buying stuff for myself until after the holidays. It was a good thing I did, too, because, sure enough, I received this DVD as a present from my mom that Christmas. The weight and importance of this version, however, didn't hit me right away, as I was more than a little distracted by the dark period in my life I was going through then, and also because I had read so much about this version that I kind of spoiled it for myself (if you've read most of my reviews, you'd know that I have a bad habit of doing that). However, as I watched this version more and more, I began to realize what a well-done, allegorical piece of cinema it really is. Yes, in other words, just like with the critics of the day, Godzilla had to wait a little bit for me to realize his true significance, and this is coming someone who'd been the biggest G-fan imaginable since childhood! The featurettes and audio commentaries for both versions in that set would help enlighten me even more and now, thanks to them and other sources, like David Kalat's incredible book, A Critical History and Filmography of Toho's Godzilla Series, and the special features on the even more amazing Criterion Collection edition, I can safely say I understand this film's importance and now have a deeper respect for Godzilla than I ever did before. It's a movie I will defend to my dying day and will forever make it known that I feel it's as important a Japanese film, or just a film period, as any movie made by Akira Kurosawa and other acclaimed filmmakers.

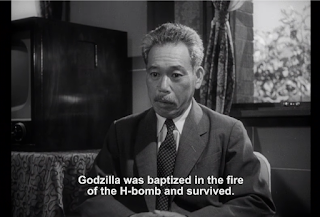

On the morning of August 13th, 1954, a Japanese fishing boat is suddenly obliterated by a mysterious and deadly force in the form of a bright flash of light. A search boat is sent out and it meets the same fate, along with a fishing boat near Odo Island that picked up some survivors. The sole survivor of this latter sinking is washed ashore on the island and, before he passes out, mentions a monster being responsible for the destruction of his boat. This, coupled with a sudden decrease in the fishing around the island, prompts an elder to suggest Godzilla, a legendary sea monster, has awakened after being dormant for centuries. A helicopter of reporters from Tokyo arrives on the island, although the journalists are initially skeptical of the stories about a creature big enough to destroy ships. But that night, after they witness an exorcism ceremony meant to keep Godzilla away, a storm hits the island... along with something else that destroys the small village and kills both the survivor and his mother. The next day, some of the surviving natives and other witnesses are brought back to Tokyo to make a report and, upon hearing them, Dr. Kyohei Yamane, one of Japan's most revered scientists, suggests that a thorough study be made of the island. At the site of the devastated village, Yamane and his group find enormous, radioactive footprints and discover that the island's main well has been contaminated. In the midst of the investigation, Godzilla briefly appears, sending the villagers and scientists into a frightened retreat, before heading back into the ocean. Back in Tokyo, Yamane presents his findings and theorizes that Godzilla was not only awakened by atomic tests but is now himself intensely radioactive. Despite an argument over keeping this information secret due to international repercussions, it is revealed to the public. Although Yamane wishes for Godzilla to be kept alive so he can be studied, the government attempts to destroy him with depth charges. This doesn't work at all, and Godzilla makes his way to Tokyo, where it becomes apparent that no weapons can stop him. The monster easily lays waste to the great city, killing thousands and injuring and contaminating thousands more with his radioactivity, and unless some method of killing him can be found, all of mankind is at risk of suffering the same fate.

When discussing Godzilla, it's imperative we also discuss the core group of people behind his conception, many of whom stayed with the series for a good chunk of it (plus, since you'll be seeing their names a lot in these reviews, it's best you get acquainted with them now). If there's one person who can be called the father of Godzilla, it's Tomoyuki Tanaka, the prolific Japanese film producer who actually came up with the idea of the Big G out of pure necessity. When a film he'd been prepping for a very long time suddenly fell-through, Tanaka had to quickly come up with a replacement in order to fill the now empty release date. Inspired by the success Warner Bros. had had the previous year with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Tanaka decided to produce his own monster movie, with the ongoing fear Japan still had about the atomic bomb nearly a decade after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the story of a recent nuclear incident involving a fishing boat, leading to the film's well-known allegory on the subject. Despite his moniker as Godzilla's true creator and the fact that he would be tied to it for the rest of his life, it was hardly the only significant work Tanaka was involved with. In a career that spanned almost 60 years, he produced over 200 films in virtually every genre, including comedy, drama, romance, and the like. He worked with Akira Kurosawa on six films, including 1980's Kagemusha, which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and in addition to the Godzilla movies, he was involved with every Toho monster and science fiction film movie made during his lifetime, often working with several or all members of the core Godzilla team on a given film. But, there's no doubt that Godzilla will always be what he's most remembered for, especially internationally, and like Albert R. Broccoli and the James Bond films, he remained involved with the franchise up until his death.

While Tanaka was Godzilla's actual creator, the man who would make it his intention to give him a soul was director Ishiro Honda. For a film that was intended to have very strong themes of nuclear holocaust, Godzilla couldn't have asked for a better director. After having been drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1938 and ending up a POW in China until the war ended, Honda had witnessed the devastation of Hiroshima when he passed through the area on his way home after the war had ended (though, exactly how much he saw and experienced firsthand is up to debate, with urban legends greatly exaggerating it). So, if there was anyone who could bring the horrors of nuclear war home and give Godzilla, whose screenplay he would also co-write, a rather chilling sense of authenticity, it was Honda. While his extreme pacifist nature may have made him naïve enough to think the film would actually end nuclear tests altogether, there's no underestimating the heart and soul he brought to it. Like Tanaka, while Honda's association with Godzilla would last the rest of his life, he actually had a very prolific filmography, often working on documentaries and war films, most notably Eagle of the Pacific in 1953. His best friend and neighbor was Akira Kurosawa, whom he mentored under and worked as an assistant early in his career. Kurosawa himself had nothing but praise and admiration for Honda, once calling him one of the most reliable and honest men he had ever known, and credited the accolades he received for accurately capturing the atmosphere of postwar Japan in the film Stray Dog to Honda's second unit work, which involved him going out and shooting footage of the still ruined sections of Tokyo from the wartime fire-bombings. So, for all you film snobs out there who feel Japanese monster movies, especially the Godzilla movies, are vastly inferior to the work of Kurosawa, just keep in mind that the very best of some of Kurosawa's films were the work of his own best friend and a man he himself had the utmost respect for.

In a typical monster movie of the times, the dashing and handsome Akira Takarada would be the hero in his role as salvage captain Ogata but, despite his being top-billed in the film's opening credits, he's actually more of a supporting character and spectator. In fact, the structure of the film has is one where the responsibility of a lead constantly shifts from one character to another and, while Ogata is the first to receive it, being called in by the Coast Guard to use his salvage expertise in figure out what happened to the boat that's destroyed at the beginning of the movie, his role in the story becomes much less significant as it goes on. While he's not a bad character at all and is made fairly likable by Takarada's natural charm, there's not much to him. He cares deeply for Emiko, whom he's seeing behind her father's back due to her arranged marriage to Dr. Serizawa, and while he does have great respect and admiration for both her father, Dr. Yamane, and Serizawa, he's intent upon asking Yamane for her hand in marriage. He's good enough to wait until Emiko breaks the news to Serizawa but, when she's unable to, he eventually decides to go ahead and ask Yamane anyway. Unfortunately, he first gets into a conversation with the doctor about his wish that Godzilla be kept alive and studied, telling him that he agrees with the military that Godzilla must be destroyed. Enraged at this, Yamane tells him to leave and storms out, pretty much dashing any hopes for the two young lovers (for that matter, I don't know why Ogata decided to wait until the moment when everyone is waiting for Godzilla to reappear in Tokyo Bay). Although he tells Emiko that he'll try to talk to Yamane about it again, it's unlikely he'll consent. In fact, the only hope the two of them have of marrying at all comes at the end of the film, when Serizawa sacrifices his life for the good of mankind. Speaking of which, the responsibility of the main character does come back around to Ogata when, after Emiko reveals that Serizawa has a device that could destroy Godzilla, he takes it upon himself to try to convince the reluctant scientist to use it. After a small scuffle between the two that leaves Ogata slightly injured, he tells Serizawa that he understands why he's reluctant to use his device, the Oxygen Destroyer, but, at the same time, asks what they're supposed to do about the crisis they're now facing. Eventually, Serizawa agrees to use the device and, when the time comes, he and Ogata go down into the ocean together to plant it. But, once again, going against what you'd expect, Ogata is not the hero who kills the monster; it's Serizawa.

Emiko Yamane (Momoko Kochi), the daughter of Dr. Yamane and who has a long-standing marriage arrangement with Dr. Serizawa, forms the second part of a love-triangle subplot in the film. She's been seeing Ogata behind her father's back and has developed a much truer, loving bond with him than she's ever had with Serizawa. She does care for Serizawa a great deal, but sees him more as an older brother rather than a lover. Wanting very much to marry Ogata, Emiko decides to tell Serizawa her feelings, hoping his consent will help sway her father in giving his blessing. But, before she can do so, Serizawa decides to show her his newest invention, the Oxygen Destroyer, swearing her to secrecy beforehand, as he doesn't want anyone to know about the device until he can find a use for it other than as a potential weapon. She vows to keep the secret, even from her father, but after Godzilla leaves Tokyo in ruins and thousands of people either dead or dying, she realizes she can't stay silent and must tell someone that there is a device which could destroy the monster. She tells Ogata and the two of them go to Serizawa's house and confront him about it. Emiko is clearly devastated about breaking her promise, breaking down crying while confessing that she did so, and after Ogata has tried to convince Serizawa that his device is the only thing that can save the world from Godzilla and the scientist, absolutely torn about what to do, puts his head down and pulls at his hair, sobbing in frustration, you can tell she has genuine sympathy for his plight. Once Serizawa agrees to use the Oxygen Destroyer and proceeds to burn his notes, Emiko cries again, as she knows from when they talked after he first showed it to her that he's going to eventually kill himself to ensure no one will know the device's secret. And after it's learned Serizawa died along with Godzilla, all Emiko, along with everyone else, can do is mourn his sacrifice and take whatever solace she can in Ogata telling her that his last words was a wish for the two of them to be happy together.

The final player in the love triangle is the least seen and yet, at the same time, most interesting by far: Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), a young, reclusive scientist who hardly ever leaves the dark, brick house which serves as his home and laboratory. Everything about him is just fascinating: his eye-patch, which you find out is a nasty memento from World War II, his aforementioned dark house and the laboratory he keeps in the basement, and his equally dark mood, and emotional distance from others, save for Emiko. It's obvious he does care for Emiko, just as Ogata does, and trusts her enough to show her the Oxygen Destroyer, a device he's created that splits oxygen atoms into liquids, suffocating every living thing in the water before disintegrating their remains. However, Serizawa is far from a mad scientist; in fact, he's absolutely horrified by what he's discovered, telling Emiko that, when he first came upon the strange energy that powers the device and experimented with it, he was so shocked that he couldn't eat for several days. He fully realizes that, if used as a weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer could be far deadlier than the H-bomb and, therefore, refuses to reveal it to the world until he can find another use for it, adding that he's willing to destroy his research papers and kill himself if he's forced to do so. His reasoning for sacrificing his life is simple: even if he does destroy his notes, the secrets of the Oxygen Destroyer will still be in his head and he can't guarantee he won't eventually be coerced by the higher-ups into divulging them. Therefore, when he realizes he must use the Oxygen Destroyer to save the world from Godzilla, he carries out his plan to ensure the secret of the device will stay hidden and, as he watches Godzilla die from its effects, he cuts his oxygen line and dies along with the monster.

It's also possible that he does this to ensure Emiko and Ogata can marry and have a happy life together. In the scene where they go to convince Serizawa to use the Oxygen Destroyer, there are subtle hints that he knows the two of them have been secretly seeing each other. He's rather happy to see Emiko when he walks down the hall towards the sitting room but, when he enters the room and sees Ogata, his mood appears to darken a little bit. When he tells the two of them to have a seat and asks what he can do for them, it's possible he's expecting them to ask for his consent on their marriage. Let's not forget that the first time you see Serizawa, he's standing at the pier, watching the research boat as it departs to investigate the wrecked village at Odo Island, and he's looking directly at Emiko and Ogata with a flower in his hand, so it's very possible he's known of their relationship for quite some time (although Ogata believes there could be a more sinister reason for his presence at the pier). But the most telling sign is when, before he commits suicide, he tells Ogata that he hopes he and Emiko will be happy together, showing that, despite his dark state of mind, he does really care for Emiko and has probably felt for a long time that she would be much happier with Ogata. This suicide, in his mind, will ensure that happiness, as well as save the world from a fate worse than the H-bomb.

Another connection between Godzilla and Akira Kurosawa is the presence of Takashi Shimura, a highly acclaimed actor who was part of Kurosawa's repertory and appeared in his legendary film, The Seven Samurai, as Dr. Kyohei Yamane. A respected Japanese paleontologist whose opinion is valued by the government officials and his fellow scientists, he's suggests that a research party be sent to make a thorough investigation of Odo Island, feeling it's not helpful for him to make any conclusions before he's visited it himself, adding that, given the deep caverns and crevices at the bottom of the ocean, there's no telling what mysteries are waiting to be discovered. After visiting Odo Island and finding various evidence, such as enormous, highly radioactive footprints and a trilobite embedded in the mud of one of them, as well as getting a very close look at Godzilla firsthand and taking a picture of his head, Yamane explains what exactly he is. He tell the government that, as evidenced by the trilobite and the sand found within its shell, Godzilla was living within caverns down in the bottom of the ocean, possibly along with others of his species, and that the H-bombs not only destroyed his habitat but inundated him with copious amounts of radioactivity. However, Yamane does not want Godzilla to be destroyed but, rather, kept alive for study. This may seem like a cliché you often come across in these types of sci-fi/monster movies but he has a good reason for it: if they can figure out how Godzilla survived direct exposure to a nuclear bomb, they could possibly save countless lives if Japan suffers another nuclear disaster. But, when the government and other scientists continue to insist Godzilla must be destroyed, Yamane becomes increasingly despondent and brooding, at one point deciding to sit in his office in the dark rather than watch the operation meant to do so with depth charges and becoming very angry at Ogata when he tells him he agrees with the consensus. But, after Godzilla all but decimates Tokyo and leaves thousands suffering, Yamane seems to realize it's best for the monster to die and makes no effort to stop Ogata and Serizawa from using the Oxygen Destroyer against him, even telling Ogata that he's counting on him. By the end of the film, Godzilla is, indeed, dead, but Yamane has not only lost Serizawa, whom he admired very much and hoped Emiko would marry one day, but also realizes it's possible that continued atomic tests might unleash another Godzilla some day.

While he doesn't do or say much of any significance, Prof. Tanabe (Fuyuki Murakami), the radiology expert, is often present during some of the most important scenes, such as the investigation of Odo Island (he warns the natives that several sections of their village, including their well, have been

contaminated and they'd best steer clear of them), Dr. Yamane's presentation of his findings to the government, and the meeting where Yamane is asked if there's any possible way to kill Godzilla. His most noteworthy moment is when, after Godzilla has decimated Tokyo, he takes a Geiger reading of a young child and then looks at Emiko and just shakes his head, indicating that this kid has no chance. Tanabe's also the one who uses his Geiger counter to locate Godzilla during the climax and, after it's all over, you can see him sitting behind Yamane when the doctor says that another Godzilla might appear one day due to repeated atomic tests, appearing to hear and understand the gravity of those words. Another character who isn't that significant in the overall story and yet, is still memorable is Hagiwara (Sachio Sakai), a journalist who, like Tanabe, is present during some of the most important scenes, getting the facts to his newspaper. He's at first skeptical when he hears talk of an enormous creature in the ocean that's causing the ship disasters but, after experiencing the typhoon on Odo Island and seeing the unsual state of the destruction, he becomes more open to the idea and tells the government officials that the destroyed houses were crushed from above, as if stepped on. He's present at the island when Godzilla makes his first appearance and, when the second official meeting on the matter erupts into chaos, you see him watching it with something of an, "Ooh, boy," type of look on his face. While working at the paper's headquarters, Hagiwara comments on a discussion two other reporters have about whether Godzilla should be studied or destroyed, saying it's a tricky subject, and is then asked by the editor to interview Dr. Serizawa after he gets a tip that Serizawa might be working on something that could be effective against Godzilla. He has to have Emiko introduce him to the reclusive scientist but, even then, he doesn't get much information out of him. Serizawa tells Hagiwara that the tip, which cited a German scientist as the source of the claim that he might have a device that could be useful, was wrong and that he knows no such scientist. And when Hagiwara then asks what it is he's working on, Serizawa refuses to say anything else. Despite this, Emiko tells Hagiwara that, now that he's broken the ice with Serizawa, he might be more open to him in the future and tells him to try again some other time. Of course, by the time he meets Serizawa again, he's unveiled the Oxygen Destroyer and the doctor sacrifices his life, prompting Hagiwara to mourn the loss along with everyone else and comfort Shinkichi, who's broken up about it as badly as Emiko.

You see firsthand the effects Godzilla's attacks have on one particular family who lives on Odo Island. Masaji (Ren Yamamoto) is a fisherman whose boat comes across several survivors from the destroyed ships, floating adrift in the ocean, and he and those with him rescue them. However, it's a short-lived rescue, as you hear that, while taking the survivors back with them to the Island, the fishing boat is destroyed in the same manner as those before and Masaji, barely alive, drifts ashore as the only survivor, mentioning something about a monster before he passes out. Masaji eventually recovers well enough to do some work around the island, but when the Tokyo reporters arrive, he's reluctant to talk to them due to the skepticism his story about a monster might draw. When he talks with Hagiwara about it, he, sure enough, doesn't exactly believe him and Masaji becomes frustrated and storms off with his younger brother, Shinkichi (Toyoaki Suzuki). That night, Godzilla comes ashore under the cover of a typhoon and crushes Masaji's hut, killing both him and his mother (Tsuruko Umano), leaving Shinkichi, who'd ran outside to see what was going on, homeless and orphaned. He's one of the islanders who's brought back to Tokyo to make an official report and during his testimony, he insists that he could just barely see an enormous creature moving in the darkness. Somewhere along the way, Shinkichi is adopted by the Yamane family, with becoming something of surrogate brother to both Emiko and Ogata. Later on, as Godzilla is leaving the smoldering Tokyo and heading back to the sea, Shinkichi quietly curses the monster, undoubtedly because he understands better than most the suffering his attack has caused. And at the end of the film, he's as broken up about Serizawa's sacrifice as Emiko, even though he never knew Serizawa. It's probably because he's thinking about how Godzilla has once again had a hand in taking a loved one away from those who care for him.

There are a couple of other memorable characters in the film. One of them is the old man on Odo Island (Kokuten Kodo) who is the first one to bring up the subject of Godzilla and, later on, when the reporters spend the night on the island, he tells Hagiwara of the legend and the ancient rituals used to keep the monster at bay. Notably, he becomes very angry when a young woman scoffs at his warnings about Godzilla, saying he's nothing but a relic from the old days, prompting him to say that if she doesn't take it more seriously, she and everyone else will become prey for Godzilla. Another, although he appears in only one scene, is Parliamentarian Oyama (Seijiro Onda), mainly because he's the center of one of the film's most topical themes with his opinion that revealing Godzilla's nuclear origin will cause an international relations nightmare, especially given how fragile such relations already were at the time. And finally, although he only appears in a moment so brief that you'd miss him if you blinked, Kenji Sahara, who would go on to act in more Godzilla and Toho sci-fi movies than any other actor, has a brief scene here as a partygoer on the boat which comes across Godzilla when he first appears in Tokyo Bay.

Those who think of Godzilla movies as nothing more than silly, campy monster flicks will probably be surprised to watch this original film and learn that it's anything but. It has a very somber, foreboding, and doom-laden atmosphere that's established right from the very beginning and is sustained all the way through. Save for a little bit of business with Hagiwara and a moment on a train where a man tells his wife that Godzilla will probably go straight for her if he comes ashore in Tokyo (to devour her, mind you), there's no humor to be found here whatsoever. The tone is made clear right from the first frames, where you hear three loud stomps, followed by Godzilla's roar as the title comes up, and then, as the opening credits scroll upwards, the film's main march plays while Godzilla continues howling and stomping. Although that theme is exciting and thrilling, the combination of it and Godzilla's roaring is unexpectedly terrifying, especially at the end of the credits when the music reaches its highest pitch and Godzilla lets out one last frightening roar before the film begins. When I first saw this version, I was a nit taken aback by how much that gives you a feeling of, "Oh, shit." And as I said, that mood stays with the film through its entirety, as you see the panic that begins to grip Tokyo as more and more ships are mysteriously destroyed, the fear of the Odo Islanders, especially in regards to their own legend about Godzilla, and the feeling of dread that overtakes Tokyo as the people wait to see when and where Godzilla will appear next.

When discussing Godzilla, it's imperative we also discuss the core group of people behind his conception, many of whom stayed with the series for a good chunk of it (plus, since you'll be seeing their names a lot in these reviews, it's best you get acquainted with them now). If there's one person who can be called the father of Godzilla, it's Tomoyuki Tanaka, the prolific Japanese film producer who actually came up with the idea of the Big G out of pure necessity. When a film he'd been prepping for a very long time suddenly fell-through, Tanaka had to quickly come up with a replacement in order to fill the now empty release date. Inspired by the success Warner Bros. had had the previous year with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Tanaka decided to produce his own monster movie, with the ongoing fear Japan still had about the atomic bomb nearly a decade after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the story of a recent nuclear incident involving a fishing boat, leading to the film's well-known allegory on the subject. Despite his moniker as Godzilla's true creator and the fact that he would be tied to it for the rest of his life, it was hardly the only significant work Tanaka was involved with. In a career that spanned almost 60 years, he produced over 200 films in virtually every genre, including comedy, drama, romance, and the like. He worked with Akira Kurosawa on six films, including 1980's Kagemusha, which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and in addition to the Godzilla movies, he was involved with every Toho monster and science fiction film movie made during his lifetime, often working with several or all members of the core Godzilla team on a given film. But, there's no doubt that Godzilla will always be what he's most remembered for, especially internationally, and like Albert R. Broccoli and the James Bond films, he remained involved with the franchise up until his death.

While Tanaka was Godzilla's actual creator, the man who would make it his intention to give him a soul was director Ishiro Honda. For a film that was intended to have very strong themes of nuclear holocaust, Godzilla couldn't have asked for a better director. After having been drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1938 and ending up a POW in China until the war ended, Honda had witnessed the devastation of Hiroshima when he passed through the area on his way home after the war had ended (though, exactly how much he saw and experienced firsthand is up to debate, with urban legends greatly exaggerating it). So, if there was anyone who could bring the horrors of nuclear war home and give Godzilla, whose screenplay he would also co-write, a rather chilling sense of authenticity, it was Honda. While his extreme pacifist nature may have made him naïve enough to think the film would actually end nuclear tests altogether, there's no underestimating the heart and soul he brought to it. Like Tanaka, while Honda's association with Godzilla would last the rest of his life, he actually had a very prolific filmography, often working on documentaries and war films, most notably Eagle of the Pacific in 1953. His best friend and neighbor was Akira Kurosawa, whom he mentored under and worked as an assistant early in his career. Kurosawa himself had nothing but praise and admiration for Honda, once calling him one of the most reliable and honest men he had ever known, and credited the accolades he received for accurately capturing the atmosphere of postwar Japan in the film Stray Dog to Honda's second unit work, which involved him going out and shooting footage of the still ruined sections of Tokyo from the wartime fire-bombings. So, for all you film snobs out there who feel Japanese monster movies, especially the Godzilla movies, are vastly inferior to the work of Kurosawa, just keep in mind that the very best of some of Kurosawa's films were the work of his own best friend and a man he himself had the utmost respect for.

In a typical monster movie of the times, the dashing and handsome Akira Takarada would be the hero in his role as salvage captain Ogata but, despite his being top-billed in the film's opening credits, he's actually more of a supporting character and spectator. In fact, the structure of the film has is one where the responsibility of a lead constantly shifts from one character to another and, while Ogata is the first to receive it, being called in by the Coast Guard to use his salvage expertise in figure out what happened to the boat that's destroyed at the beginning of the movie, his role in the story becomes much less significant as it goes on. While he's not a bad character at all and is made fairly likable by Takarada's natural charm, there's not much to him. He cares deeply for Emiko, whom he's seeing behind her father's back due to her arranged marriage to Dr. Serizawa, and while he does have great respect and admiration for both her father, Dr. Yamane, and Serizawa, he's intent upon asking Yamane for her hand in marriage. He's good enough to wait until Emiko breaks the news to Serizawa but, when she's unable to, he eventually decides to go ahead and ask Yamane anyway. Unfortunately, he first gets into a conversation with the doctor about his wish that Godzilla be kept alive and studied, telling him that he agrees with the military that Godzilla must be destroyed. Enraged at this, Yamane tells him to leave and storms out, pretty much dashing any hopes for the two young lovers (for that matter, I don't know why Ogata decided to wait until the moment when everyone is waiting for Godzilla to reappear in Tokyo Bay). Although he tells Emiko that he'll try to talk to Yamane about it again, it's unlikely he'll consent. In fact, the only hope the two of them have of marrying at all comes at the end of the film, when Serizawa sacrifices his life for the good of mankind. Speaking of which, the responsibility of the main character does come back around to Ogata when, after Emiko reveals that Serizawa has a device that could destroy Godzilla, he takes it upon himself to try to convince the reluctant scientist to use it. After a small scuffle between the two that leaves Ogata slightly injured, he tells Serizawa that he understands why he's reluctant to use his device, the Oxygen Destroyer, but, at the same time, asks what they're supposed to do about the crisis they're now facing. Eventually, Serizawa agrees to use the device and, when the time comes, he and Ogata go down into the ocean together to plant it. But, once again, going against what you'd expect, Ogata is not the hero who kills the monster; it's Serizawa.

Emiko Yamane (Momoko Kochi), the daughter of Dr. Yamane and who has a long-standing marriage arrangement with Dr. Serizawa, forms the second part of a love-triangle subplot in the film. She's been seeing Ogata behind her father's back and has developed a much truer, loving bond with him than she's ever had with Serizawa. She does care for Serizawa a great deal, but sees him more as an older brother rather than a lover. Wanting very much to marry Ogata, Emiko decides to tell Serizawa her feelings, hoping his consent will help sway her father in giving his blessing. But, before she can do so, Serizawa decides to show her his newest invention, the Oxygen Destroyer, swearing her to secrecy beforehand, as he doesn't want anyone to know about the device until he can find a use for it other than as a potential weapon. She vows to keep the secret, even from her father, but after Godzilla leaves Tokyo in ruins and thousands of people either dead or dying, she realizes she can't stay silent and must tell someone that there is a device which could destroy the monster. She tells Ogata and the two of them go to Serizawa's house and confront him about it. Emiko is clearly devastated about breaking her promise, breaking down crying while confessing that she did so, and after Ogata has tried to convince Serizawa that his device is the only thing that can save the world from Godzilla and the scientist, absolutely torn about what to do, puts his head down and pulls at his hair, sobbing in frustration, you can tell she has genuine sympathy for his plight. Once Serizawa agrees to use the Oxygen Destroyer and proceeds to burn his notes, Emiko cries again, as she knows from when they talked after he first showed it to her that he's going to eventually kill himself to ensure no one will know the device's secret. And after it's learned Serizawa died along with Godzilla, all Emiko, along with everyone else, can do is mourn his sacrifice and take whatever solace she can in Ogata telling her that his last words was a wish for the two of them to be happy together.

The final player in the love triangle is the least seen and yet, at the same time, most interesting by far: Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), a young, reclusive scientist who hardly ever leaves the dark, brick house which serves as his home and laboratory. Everything about him is just fascinating: his eye-patch, which you find out is a nasty memento from World War II, his aforementioned dark house and the laboratory he keeps in the basement, and his equally dark mood, and emotional distance from others, save for Emiko. It's obvious he does care for Emiko, just as Ogata does, and trusts her enough to show her the Oxygen Destroyer, a device he's created that splits oxygen atoms into liquids, suffocating every living thing in the water before disintegrating their remains. However, Serizawa is far from a mad scientist; in fact, he's absolutely horrified by what he's discovered, telling Emiko that, when he first came upon the strange energy that powers the device and experimented with it, he was so shocked that he couldn't eat for several days. He fully realizes that, if used as a weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer could be far deadlier than the H-bomb and, therefore, refuses to reveal it to the world until he can find another use for it, adding that he's willing to destroy his research papers and kill himself if he's forced to do so. His reasoning for sacrificing his life is simple: even if he does destroy his notes, the secrets of the Oxygen Destroyer will still be in his head and he can't guarantee he won't eventually be coerced by the higher-ups into divulging them. Therefore, when he realizes he must use the Oxygen Destroyer to save the world from Godzilla, he carries out his plan to ensure the secret of the device will stay hidden and, as he watches Godzilla die from its effects, he cuts his oxygen line and dies along with the monster.

It's also possible that he does this to ensure Emiko and Ogata can marry and have a happy life together. In the scene where they go to convince Serizawa to use the Oxygen Destroyer, there are subtle hints that he knows the two of them have been secretly seeing each other. He's rather happy to see Emiko when he walks down the hall towards the sitting room but, when he enters the room and sees Ogata, his mood appears to darken a little bit. When he tells the two of them to have a seat and asks what he can do for them, it's possible he's expecting them to ask for his consent on their marriage. Let's not forget that the first time you see Serizawa, he's standing at the pier, watching the research boat as it departs to investigate the wrecked village at Odo Island, and he's looking directly at Emiko and Ogata with a flower in his hand, so it's very possible he's known of their relationship for quite some time (although Ogata believes there could be a more sinister reason for his presence at the pier). But the most telling sign is when, before he commits suicide, he tells Ogata that he hopes he and Emiko will be happy together, showing that, despite his dark state of mind, he does really care for Emiko and has probably felt for a long time that she would be much happier with Ogata. This suicide, in his mind, will ensure that happiness, as well as save the world from a fate worse than the H-bomb.

Another connection between Godzilla and Akira Kurosawa is the presence of Takashi Shimura, a highly acclaimed actor who was part of Kurosawa's repertory and appeared in his legendary film, The Seven Samurai, as Dr. Kyohei Yamane. A respected Japanese paleontologist whose opinion is valued by the government officials and his fellow scientists, he's suggests that a research party be sent to make a thorough investigation of Odo Island, feeling it's not helpful for him to make any conclusions before he's visited it himself, adding that, given the deep caverns and crevices at the bottom of the ocean, there's no telling what mysteries are waiting to be discovered. After visiting Odo Island and finding various evidence, such as enormous, highly radioactive footprints and a trilobite embedded in the mud of one of them, as well as getting a very close look at Godzilla firsthand and taking a picture of his head, Yamane explains what exactly he is. He tell the government that, as evidenced by the trilobite and the sand found within its shell, Godzilla was living within caverns down in the bottom of the ocean, possibly along with others of his species, and that the H-bombs not only destroyed his habitat but inundated him with copious amounts of radioactivity. However, Yamane does not want Godzilla to be destroyed but, rather, kept alive for study. This may seem like a cliché you often come across in these types of sci-fi/monster movies but he has a good reason for it: if they can figure out how Godzilla survived direct exposure to a nuclear bomb, they could possibly save countless lives if Japan suffers another nuclear disaster. But, when the government and other scientists continue to insist Godzilla must be destroyed, Yamane becomes increasingly despondent and brooding, at one point deciding to sit in his office in the dark rather than watch the operation meant to do so with depth charges and becoming very angry at Ogata when he tells him he agrees with the consensus. But, after Godzilla all but decimates Tokyo and leaves thousands suffering, Yamane seems to realize it's best for the monster to die and makes no effort to stop Ogata and Serizawa from using the Oxygen Destroyer against him, even telling Ogata that he's counting on him. By the end of the film, Godzilla is, indeed, dead, but Yamane has not only lost Serizawa, whom he admired very much and hoped Emiko would marry one day, but also realizes it's possible that continued atomic tests might unleash another Godzilla some day.

One of the major contributing factors to the film's mood is the way it looks. This is one of the darkest, grittiest-looking black-and-white movies I've ever seen, with a lot of contrast and deep shadows in the cinematography, especially in the many nighttime scenes. Not only does this extreme darkness make Godzilla himself all the more frightening when he attacks but it gives the movie a nightmarish vibe all around, with a sense that these people are trapped in a dark void they can't escape, that inescapable doom is always hanging over them. That sense is very palpable in scenes of extreme urgency, like the typhoon on Odo Island and the sequence of people desperate to reach shelter before Godzilla's first attack on Tokyo, and also in quiet, uneasy scenes, like the introduction to the Odo Islanders as they sit on a beach, contemplating the cause of the shipping disasters, a scene that's made all the more surreal-looking in its dread with the day-for-night cinematography, and the darkness inside Dr. Serizawa's home. There's also a kind of gritty realism to the way the movie looks, with even the most pristine, remastered prints, including the Criterion Collection Blu-Ray release, having a fair amount of grain and scratches, as if what we're watching is

old newsreel footage rather than a movie. Some have complained about this, attributing it to sloppy preservation on Toho's part. but the

film has always looked like this due to the very soft, sensitive film

stock that was used at the time, which often got scratched when it was run through the editing machine, and the less than spotless conditions of

the studio, including the editing room itself, which was very dusty.

Even when he's not onscreen, the fear and dread Godzilla creates is palpable. The unexpected and mysterious flashes of blinding light that appear out of nowhere and utterly wipe out these ships give you a frightening taste of the unknown, and then, when we get to Odo Island, we learn of the legend of Godzilla and the rituals that were once used to keep him at bay, as well as hear Masaji say he's sure it was some sort of enormous creature that destroyed his fishing boat. When the typhoon strikes the island that night, you get the ominous feeling that the islanders have more to fear than lightning and pounding winds, a feeling Masaji seems to have as he lies in bed, looking around the room and rubbing his head anxiously. We then begin to hear Godzilla's thundering footsteps within the storm and, when Shinkichi runs outside to find the source of the noise, Masaji follows him and hears him scream for him outside. There's a flash of lightning and Masaji recoils in fear after looking out the window, no doubt getting a clear look at Godzilla, and runs back to his mother inside, where the two of them die when the roof caves in. It's as though Godzilla knew Masaji got away from the fishing boat when he destroyed it and followed him back to Odo Island to finish the job. And let's also not forget how, not long after Shinkichi leaves the island to live in Tokyo with the Yamane family, Godzilla appears in the bay, as if he's following every member of Masaji's family. Going back to Godzilla's footsteps, as a continual tip off that he's nearby, they create an atmosphere of urgency and fear the minute they're heard, which is often long before he's actually seen. We hear them as soon as the alarm is sounded while Yamane and his colleagues are studying the wrecked village and they continue as they and the villagers run up into the hills to get a look at him, unaware of what they're up against. Eerily, during the moment following his first appearance where they see his enormous footprints leading to the ocean, the sound of his footsteps can be heard off in the distance, reminding them that he may be gone but he's still in the area. During the scene at the boat party near Tokyo, the footsteps start up in the midst of the festivities, telling us that they're about to be cut short, and, most foreboding of all, we hear them coupled with the sound of an alarm when Yamane and everyone else realizes Godzilla's approaching Tokyo. The scene right after that, where you see people attempting to run for safety, all while still hearing Godzilla's footsteps and the continuously blaring alarm, which are now coupled with the sound of police sirens, has a feeling of impending doom, that most of these people probably won't make it to shelter before Godzilla arrives (which is indeed the case).

Godzilla's attacks and how people respond to them are treated with a sense of reality in this film, as if it's an actual disaster, and gives you an idea of would it be like if a gigantic, unstoppable monster like him did appear. When the ship is destroyed at the beginning, we see the immediate response by the Coast Guard, as they call in Ogata to help figure out what happened, while the owner of the steamship company frantically runs into the situation room and asks the officials what could have happened, a question they don't know the answer to. After the search boat suffers the same fate as the fishing boat, we see how this news is beginning to circulate across the country, with scenes of reporters on phones, reporting that another disaster has happened, and we also start to see the real human drama, as the distraught families of the ships' crews crowd the Coast Guard's headquarters, demanding to know what's being done to find any survivors. All the officials can do is assure them that everything that can be done is being done, with more ships and helicopters being used as part of the search efforts. However, even this is met with skepticism by the frantic families, with one man insisting that the number of ships being used isn't nearly enough. When several survivors are picked up by the fishing boat near Odo Island, the Coast Guard reports this to the families and they, of course, immediately ask which ship they're from. They're told they don't know but the names will be released as soon as possible. Right after the one official says that, an officer comes in and hands him a piece of paper, prompting the families to rush the situation room, thinking the names have just come through. They have to be all but restrained at the door and we then learn that it's not good news at all, that the fishing boat which picked up the survivors has also been destroyed. Speaking of which, when Masaji washes ashore on the island while drifting on a piece of debris, we see his family and friends rush to his aide, as well as the sound of a woman, undoubtedly his distraught mother, calling his name. One man picks Masaji up and smacks the side of his face, momentarily bringing him to consciousness and allowing him to mumble that something destroyed his boat before passing out again, prompting everyone to yell, demanding to learn what happened, while that one guy tries to shake Masaji awake again.

I really like the setting of Odo Island in the first act of the film, in how it's this small little place in the Pacific that's home to a number of humble fishermen and their families, living a quaint existence in a tiny village there. It serves as sort of a halfway point between Japan's ancient, folkloric past, as they are people living in the modern age but are totally cut off from it, instead living in rather simple, somewhat primitive conditions. The old legend of Godzilla is still a part of their lives, although the younger people on the island don't take it as seriously as the older folks, with this ritualistic dance seen at one point being all that's left of an ancient exorcism ceremony and even then, they seem to do it now mainly for tradition's sake. Going back to the notion of this film's gritty realism, the filmmakers shot the exteriors of Odo Island at a very remote peninsula in the Mie Prefecture, with Ishiro Honda using many of the local villagers as extras in the big crowd scenes. Moreover, the dance ceremony was performed by some of the villagers, who even danced to music that was performed live (although, the music heard in the actual film was the work of composer Akira Ifukube).

The film also gives you an interesting look at postwar Tokyo and how things seem to be progressing quite nicely with them. The city is shown to be brightly lit at night and positively bustling, there are party boats where people can go to drink and dance the night away, and there are some households which prove that certain families are doing quite well in terms of their wealth and social standing. One such place is the Yamane home, which we don't see a lot of but we can tell that it's a fairly big, roomy, well-furnished place, with Yamane himself having a nice study with a model Stegosaurus skeleton on his desk (the fact that they have a television set, which was quite rare in Japan at the time, is a sign of their wealth and prosperity in and of itself). One place that sticks out as being far from the norm, though, is Dr. Serizawa's home, which is a brick building that has a European look and feel to it and, which as I mentioned earlier, is very dark on the inside, even though it's almost always a bright, sunny day outside. And while Serizawa is not a mad scientist at all, his laboratory, which he keeps down in the basement, might have you think otherwise, as it is very Frankenstein-like, full of all sorts of high-tech-looking equipment, beakers and test-tubes, and various fish tanks, as well as a large bookcase to the left of the door. Heck, when he gives Emiko a demonstration of the Oxygen Destroyer, he throws a large switch in a manner that wouldn't look out of place in a classic mad scientist movie. He also has a television set down there rather than upstairs, which itself is strange.

Alright, now that we've got all that out of the way, let's talk about the real reason why we're here: the King of the Monsters himself, my boy Godzilla. To talk about Godzilla is really to talk about Haruo Nakajima, the stuntman who literally brought the Big G to life and would go on to do so for almost the next twenty years. While Nakajima would be able to use his physical prowess and expression to create a personality for Godzilla in the later films, here, he wasn't able to do that much because this first suit was very arduous to wear. It wasn't originally built for him, for one thing, and weighed over 200 pounds, limiting his movements to where he could only walk in a straight line. Plus, because of the bright studio lights needed to shoot the special effects scenes, the temperature inside the suit would get up to 130 degrees, meaning Nakajima could be in there for only three minutes at a time and did pass out several times during filming. As a result, Godzilla doesn't have much of a real character here, and is primarily just a rampaging beast, but that actually helps the movie get its point across. Make no mistake, this isn't the wrestling, karate-chopping Godzilla you would see beating up monsters in later films; this Godzilla is a bringer of death and destruction, an ancient force of nature that's striking back against man for the sins of their arrogance. Moreover, the legend the Odo Islanders tell of him feels very real when you see him methodically and matter-of-factly going through Tokyo, destroying everything he sees, as he does come off as an angry god who's raining fire down upon those who have displeased him. And most chillingly, there's very little emotion in him as he does so. His face is blank for the most part and, while he does have animalistic moments, like when he roars at a ringing clock tower, as though he thinks it's challenging him, for the most part, his actions are those of something powerful and otherworldly that's passing severe judgment without any hesitation, remorse, or pity.

Here's an interesting question: how did Godzilla get his name? There's some debate as to exactly how it came about, and we'll tackle the first part of the question here. His Japanese moniker, "Gojira," is a combination of the Japanese words for "gorilla" and "whale," which Haruo Nakajima himself claimed was simply the winner of a contest Toho held a contest to name the monster. Shigeru Kayama, writer of the initial story which Ishiro Honda and Takeo Murata then re-wrote into the final screenplay, however, told a differently story in his memoirs, claiming that Tomoyuki Tanaka's original concept was of a hideous creature that was very much a cross between a gorilla and a whale but then, Tanaka saw The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and decided on a dinosaur-monster instead, with the name Gojira staying unchanged. The problem there is that Tanaka is said to have only got the idea to make a monster movie at all after he saw The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, and that the first draft of the script was simply titled G, which stood for Giant. One popular story surrounding the name is that it was the nickname of a big, burly stagehand working at Toho at the time and that Tanaka decided the name would be suitable for a monster. Not only has not one single photograph of this man ever surfaced, nobody claiming to be him ever came forward, which you'd think would have happened after Godzilla became so popular. In his and Ed Godziszewski's audio commentary on the Classic Media release, Steve Ryfle mentions a 2003 Japanese TV special that claimed to have identified this man as Shiro Amikura, a bit player under contract to Toho in the 50's, but this has never been 100% verified, with many finding it hard to believe that the source of Godzilla's name could have remained anonymous for decades. Furthermore, the story surrounding this unidentified guy continuously changes, as sometimes it's said he was a PR man rather than a stagehand and such. Kim Honda, the wife of Ishiro Honda, has said it was probably just a rumor that was spread around Toho by the bored stagehands and might have even become something of an inside joke amongst the filmmakers. So, in short, the answer to the "Gojira" side of the question remains elusive.

The Godzilla movies, even the best of them, tend to get mocked for the special effects work, as for many, the sight of a guy in a monster suit trashing a miniature city looks silly and not at all convincing. The work in these films are often compared to the impressive stop-motion work by effects legends Willis O'Brien and Ray Harryhausen (the latter of whom had a major disdain for Godzilla his entire life) and are then dismissed as cheap and low-grade. Even during the original film's limited American theatrical release in 2004, Roger Ebert, who'd always made his dislike for Godzilla known, felt the need to compare the film's effects to the state of the art computer effects of today, saying, "Godzilla and the city he destroys are equally crude. Godzilla at times looks uncannily like a man in a rubber suit, stomping on cardboard sets, as indeed he was, and did. Other scenes show him as a stuffed, awkward animatronic model. This was not state-of-the-art even at the time; King Kong (1933) was much more convincing." I mean no disrespect to Ebert, as he did at least note the film's significance in the grand scheme of things (although, in a backhanded way, calling it a "bad movie" that had, "Earned its place in history," regardless), but that kind of snobbish attitude has always irritated me. For one, if you're complaining about a movie from the 50's not having effects that are on the level of today's, then you're just a fool. Also, as much I love King Kong, those effects, as ground-breaking as they were back then, as well as still impressive now when you realize the work that went into them, don't look realistic when compared to the effects capabilities of today, either. Bu,t no one dares say that because that film is considered an all-time classic, whereas Godzilla, despite the respect the original film and, in more recent years, the series as a whole do get nowadays, has always been looked down upon by the "esteemed" film critics. Does a film have to be state-of-the-art in terms of its effects in order to be good? No, it doesn't, but it's like some people feel that all monster movies made after King Kong had to aspire to that film's quality standard. Did it ever occur to them that not all movies either have the same ambitions or have the resources necessary to aspire to the heights King Kong reached? And finally, just because Godzilla didn't employ stop-motion effects doesn't mean that its effects weren't noteworthy in another way. Except for a couple of lost King Kong films that were made in Japan in the late 30's, I can't think of a monster movie that had used the technique of a man in a suit on a miniature set before. It's possible there's some obscure one that I don't know of but, for the time, this was practically something new. And even if the Godzilla suit and the puppets don't always look realistic (which, I've admitted, they don't), the sweat, blood, and tears that went into creating them, as well as the craftsmanship of the miniatures and some of the optical effects, are to be commended. Plus, the Japanese focus more on the beauty of something rather than realism and, in that regard, I think the work in this film and many of the others knock it out of the park. If you disagree, that's fine. That was just my inner fanboy rage coming out to defend something I love and which I feel gets some unfair criticism. I apologize for the rant.

The comparisons to King Kong and other stop-motion monster movies of the era are ironic, as Eiji Tsuburaya, the father of Japanese special effects and another key member of the core Godzilla team, loved King Kong and wanted very much to use the stop-motion for Godzilla, but time and budget constraints wouldn't allow it (plus, he realized neither he nor anyone else in Japan at the time knew how to do that type of effects work). Instead he opted for the man-in-suit technique, leading to a new type of effects work altogether, dubbed "suitmation." You really have to applaud the guy for using his ingenuity and imagination to get around a big problem rather than just giving up altogether. Now, again, I fully admit that the Godzilla suit and puppets aren't always the most realistic-looking, as you can see the folds in the costume in some shots and I've gone into how the puppet heads are awkward and don't match the suit's head. But, for me, the seriousness of the story and the tone helps and, again, so does the way the suit is photographed at night, with lots of shadows, which are made all the more effective in black and white, and low angles. The model buildings are also very well-designed and constructed. Yes, sometimes they do look like miniatures but, even in those shots, I still can't help but admire the art and craftsmanship that went into creating them; plus, I've always gotten a bit more pumped from real, tangible models getting stomped, crushed, and blown up by guys in suits rather than watching something digital or even stop-motion. No matter how well-done and spectacular those latter types of effects look, it's more believable to me when something is actually being smashed and burnt in front of the camera as it happens, rather than it being done one frame at a time or on a computer in post. The optical effects are the most impressive of all, such as the matte paintings of Godzilla's footprints on the hillside next to the destroyed village on Odo Island, as well as the shot of his footprints leading from the shore to the ocean after he makes his first appearance. The compositing shots used to integrate him into shots of fleeing people and, at times, real shots of Tokyo (there's one of him peering over the top of a building that was

achieved by combining the puppet head with a shot of a real building), also look very impressive, as do the effects of his spines lighting up before he fires his atomic breath, which I'm pretty sure was achieved simply through animation as well as through physical effects. And finally, I admire the ingenuity of some of the effects, such as how they achieved Godzilla melting the electrical towers with his atomic breath by building the towers out of wax and then heating them up. To sum up, if you still can't get past some of these effects, fair enough, but I think they're pretty damn good and, along with the effects in most of the other films, deserve more respect.

Any problems I have with this movie are very minor and nitpicky. Aside from the aforementioned issues with some of the special effects, one problem I have to mention is the occasionally choppy editing. The biggest example is when Emiko and Hagiwara head out to see Dr. Serizawa, as we see a shot of the car the two of them are driving, when suddenly, we cut to a shot of Ogata and Shinkichi riding to the Yamane house on a motorcycle. We see them stop and push the bike into the garage, before we cut back to virtually the same shot of the car. That bit with the bike not only wasn't necessary, since before Emiko and Hagiwara leave, Ogata tells her that he's going to help Shinkichi with his studies, which already suggests that the two of them will be heading to the Yamane house, where Shinkichi is now living, but the sudden cut in the middle of the shot of the car can really throw the view off. There's another bit of choppy editing in the scene where Ogata tells Emiko that he's decided to now ask for her father's consent to their marriage. Emiko smiles at Ogata and then, upon hearing Yamane return after a meeting, there's an abrupt cut to her standing up to go meet him at the door. Again, it's not a big deal, and also isn't as jarring as that previous edit, but it is something I've always noticed. And on the dramatic side of things, as Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski mention on their audio commentary for the Classic Media DVD release, the idea of the military constructing such a huge, all-encompassing electrical barrier around Tokyo in, at most, just a few days after Godzilla's first attack is a major plothole, one which is actually corrected in Godzilla, King of the Monsters.

This leads into the scene where we get our first taste of the mysterious research Serizawa is tight-lipped about when speaking with Hagiwara. He asks Emiko if she would like to see it but then swears her to secrecy, saying he's risking his life on it. He then leads her down to the basement where he keeps his laboratory, the sight of which amazes her. She then walks over to one fish tank in particular, as he approaches it with a bowl and, looking at the numerous fish inside, as well as glancing at Emiko, he drops a little speck from the bowl down into the tank. He then walks over to the other side of the tank and throws a switch, which causes the equipment to emit a bizarre, screeching sound. Emiko looks at the fish tank, when Serizawa tells her to stand back, and they both watch as the tank's water becomes cloudy. Suddenly, Emiko lets out a horrified scream and hides her eyes in Serizawa's shoulder, as a loud boom vibrates through the lab and Serizawa stares at the tank with a knowing, appalled expression. They then walk out of the lab and, as they head back up the stairs, Serizawa again asks Emiko to keep what she's just seen a secret.

That night, Emiko returns home and everyone sits and mills around in the living room, when they suddenly hear an alarm followed by the sound of Godzilla's footsteps. Realizing what's happening, they evacuate the house, as Godzilla is shown emerging from Tokyo Bay again. Some soldiers onshore on him but he isn't fazed by this and continues wading towards the shoreline, as the civilians attempt to make it to safety zones. Yamane and his family are unable to make it past a barricade, so Yamane tells a soldier to inform his commanding officer that shining searchlights in Godzilla's face will only enrage him, but the soldier says he can't leave his post. Ogata suggests to Yamane that they head up a nearby hill, as Godzilla, having come ashore, heads for Tokyo's Shinagawa district, as hundreds of people attempt to get out of harm's way. He plows through various houses and other structures as he makes his way towards the railroad. He steps right on the track and in the path of an oncoming train, which smashes into the side of his foot, violently derailing the cars. As the passengers climb out the windows, Godzilla picks one up one of the cars in his mouth and then drops it, smashing into down amongst the wreckage. As frightened and injured people watch from cover, he stomps on one of the train cars before moving on, causing more damage and sending more people fleeing. He stops again in front of a bridge, which he smashes with some crumpled pieces of wreckage he grabs onto and pulls up, and then pushes the side of a bit with his tail. Godzilla then unexpectedly heads back to the ocean, roaring as he goes, as Yamane and the others on the hill watch.

In preparation for Godzilla's inevitable second attack, the military intends to erect an enormous barrier of barbed wire all along the coast and then conduct thousands of volts of electricity through it. They also plan to evacuate everyone outside the perimeter and everyone within 1,600 feet on the inside, with the defense forces and Navy carrying out their own duties in accordance with a security plan. After doing everything they can to evacuate those in harm's way, bring in the heavy artillery, and checking to make sure the electrical barricade works, the military and everyone hunkers down to wait as night falls. They don't have to wait long before a news bulletin announces that Godzilla is heading back to the Tokyo-Yokohama coastline, and while guards on a concrete barrier near the coast illuminate the ocean with searchlights, tanks and other military equipment is driven into place. He then emerges from Tokyo Bay yet again and wades towards the shore. As he does, soldiers manning a row of cannons point their turrets upwards at him. He comes ashore and heads towards the barricade, reaching the towers. A technicians throws a switch, activating the electricity, but Godzilla plows through the wires without being fazed by the enormous charge and, in response, the military fires on him with their machine guns and turrets. With everything exploding on and around him, Godzilla turns to his left and easily tears down the tower there. The military continues firing on him as he then destroys the tower on his right and, not at all affected by this onslaught and with the military blasting around his feet, he unveils his atomic breath for the first time. He blasts two other towers, heating them to the point where they slag and fall over on themselves. Now, with nothing else in his way, Godzilla towards the defenseless city and, to put it simply, all hell breaks loose. People run for their lives as he ignites a couple of houses with his atomic breath, walks past the burning structures, turns to look at them briefly, and then turns forward and ignites more structures. Some civilians and soldiers flee into the streets but they're caught up in another blast and scream in agony as they're burned alive. Fire engines race down the street to the site, as Godzilla continues igniting houses and whole blocks. He blows up two gas tanks, causing one of the fire engines to crash into the side of a building (the model there looks terribly fake, I must admit), while another flops over and crash through a storefront. Godzilla begins walking forward again, his foot stepping right through the roof of a warehouse, as people run down the street (one guy actually trips and falls when Godzilla's feet are just little more than a meter away from him), many being forced to run down an alley in order to just avoid being crushed.

As Godzilla continues heading further downtown, several tanks attempt to stop his advance, firing multiple rounds and hitting him in the chest, stomach, and other areas, but he just shakes them off. Realizing it's not working, the tanks turn around and retreat, as Godzilla fires a stream of atomic breath right at the street, causing an explosion and then a line of fire that heads down the road behind the tanks (there are a number of wires suspended above the street in this scene but I don't know if they're meant to be power lines or are what the model tanks are traveling along). Hearing how badly things are going, with fires raging in the Shibaura district and spreading further, and that the defenses at Fudanotsuji have been destroyed, making any further action impossible, the command center orders all units to initiate Security Command Code 129, abandoning their attacks and concentrating on extinguishing the fires and rescuing civilians caught in the danger zone. Several soldiers hear these orders over the radio of a squad car, when Godzilla suddenly peeks his head over a nearby building with a roar. The soldiers outside the car run for cover, but those inside are killed instantly when Godzilla fires his atomic breath right at the car, blowing it up. A group of people watch the carnage from the heart of the city, but when Godzilla ignites the top and bottom of a tower, which then topples over with a loud crash, they run for it. With the streets completely empty of people, Godzilla continues his advance, roaring behind an enormous birdcage that's likely part of a zoo, smashing the top of a warehouse with his tail, moving forward and toppling over and crushing more buildings, igniting some more, and trapping a mother and her children in the shadow of one building. Several soldiers take cover as Godzilla, hearing the chiming of a clock tower, snarls a challenge at it and then tears it apart. Television reporters cover the disaster from a nearby tower, with one reporter almost to the point of passing out from fear as he comments, "This is absolutely unbelievable, yet it's unfolding before our very eyes. Godzilla's leaving a sea of flames in its wake! Owari-cho, Shinbashi, Tamachi, Shiba, Shibaura, all a sea of flames! Godzilla's on the move! It appears headed for Sukiyabashi. For those watching at home, this is no play or movie. This is real, the story of the century! Will the world be destroyed by a two million-year old monster?" Godzilla presses onward, passing over a small bridge and into the heart of the city, crushing a set of raised train tracks and smashing the side of a theater (the very theater where the film had its premier) with his tail in a short partially created through stop-motion, before turning to his right and igniting another fire in the streets. The personnel inside the command center evacuate and head for the shelter, as the building begins to shake and groan before the interior collapses in on itself as Godzilla passes by. In an iconic shot, he walks behind the Diet Building, stops for a second, and then turns and plows straight through another building.

He spots the news tower and marches towards it as the reporters continue commenting, as well as filming and photographing him. Godzilla grabs the tower and bites into it, as the one reporter, realizing he and his colleagues are doomed, comments as quickly as he can before finally signing off. The tower bends in the middle and tumbles to the ground, the reporters falling to their deaths. Dr. Serizawa is shown watching another television broadcast of the attack from the safety of his laboratory, as a reporter comments that Godzilla is, "Proceeding from Ueno to Asakusa, possibly heading for the sea." Indeed, apparently satisfied with the destruction he's caused, Godzilla begins heading back towards the ocean. But, before he goes, and as Yamane, Emiko, Ogata, and Shinkichi, who quietly calls him a "damned beast," watch along with a crowd of spectators, he grabs the underside of a large bridge and turns it over, causing enormous waves that threaten to overturn some ships in the nearby harbor. The Japanese Air Force then makes one last effort to stop him, as a squadron of fighter jets fly in and fire upon him as he heads back out into the sea. This attack proves to be even more ineffective and pointless as the others, mainly because not one of the missiles fired actually hits Godzilla but instead they all just streak past him without even grazing him. He sort of swipes his hands at any missiles that get close but, overall, he's not really paying any attention, as he heads into deep water and finally plunges beneath the surface. Although the onlookers cheer this, as the jets break off the attack, they quickly realize they have nothing to celebrate, given that Tokyo is in fiery ruins and Godzilla is still alive and could return at any time.